I don't know how CPUs work so I simulated one in code

A few months ago it dawned on me that I didn’t really understand how computers work under the hood. I still don’t understand how modern computers work.

However, after making my way through But How Do It Know? by J. Clark Scott, a book which describes the bits of a simple 8-bit computer from the NAND gates, through to the registers, RAM, bits of the CPU, ALU and I/O, I got a hankering to implement it in code.

While I’m not that interested in the physics of the circuitry, the book just about skims the surface of those waters and gives a neat overview of the wiring and how bits move around the system without the requisite electrical engineering knowledge. For me though I can’t get comfortable with book descriptions, I have to see things in action and learn from my inevitable mistakes, which led me to chart a course on the rough seas of writing a circuit in code and getting a bit weepy about it.

The fruits of my voyage can be seen in simple-computer; a simple computer that’s simple and computes things.

Example programs

It is quite a neat little thing, the CPU code is implemented as a horrific splurge of gates turning on and off but it works, I’ve unit tested it, and we all know unit tests are irrefutable proof that something works.

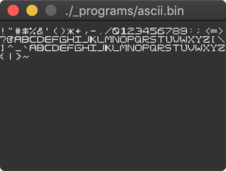

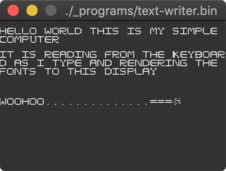

It handles keyboard inputs, and renders text to a display using a painstakingly crafted set of glyphs for a professional font I’ve named “Daniel Code Pro”. The only cheat bit is to get the keyboard input and display output working I had to hook up go channels to speak to the outside world via GLFW, but the rest of it is a simulated circuit.

I even wrote a crude assembler which was eye opening to say the least. It’s not perfect. Actually it’s a bit crap, but it highlighted to me the problems that other people have already solved many, many years ago and I think I’m a better person for it. Or worse, depending who you ask.

But why you do that?

“I’ve seen thirteen year old children do this in Minecraft, come back to me when you’ve built a REAL CPU out of telegraph relays”

My mental model of computing is stuck in beginner computer science textbooks, and the CPU that powers the gameboy emulator I wrote back in 2013 is really nothing like the CPUs that are running today. Even saying that, the emulator is just a state machine, it doesn’t describe the stuff at the logic gate level. You can implement most of it using just a switch statement and storing the state of the registers.

So I’m trying to get a better understanding of this stuff because I don’t know what L1/L2 caches are, I don’t know what pipelining means, I’m not entirely sure I understand the Meltdown and Spectre vulnerability papers. Someone told me they were optimising their code to make use of CPU caches, I don’t know how to verify that other than taking their word for it. I’m not really sure what all the x86 instructions mean. I don’t understand how people off-load work to a GPU or TPU. I don’t know what a TPU is. I don’t know how to make use of SIMD instructions.

But all that is built on a foundation of knowledge you need to earn your stripes for, so I ain’t gonna get there without reading the map first. Which means getting back to basics and getting my hands dirty with something simple. The “Scott Computer” described in the book is simple. That’s the reason.

Great Scott! It’s alive!

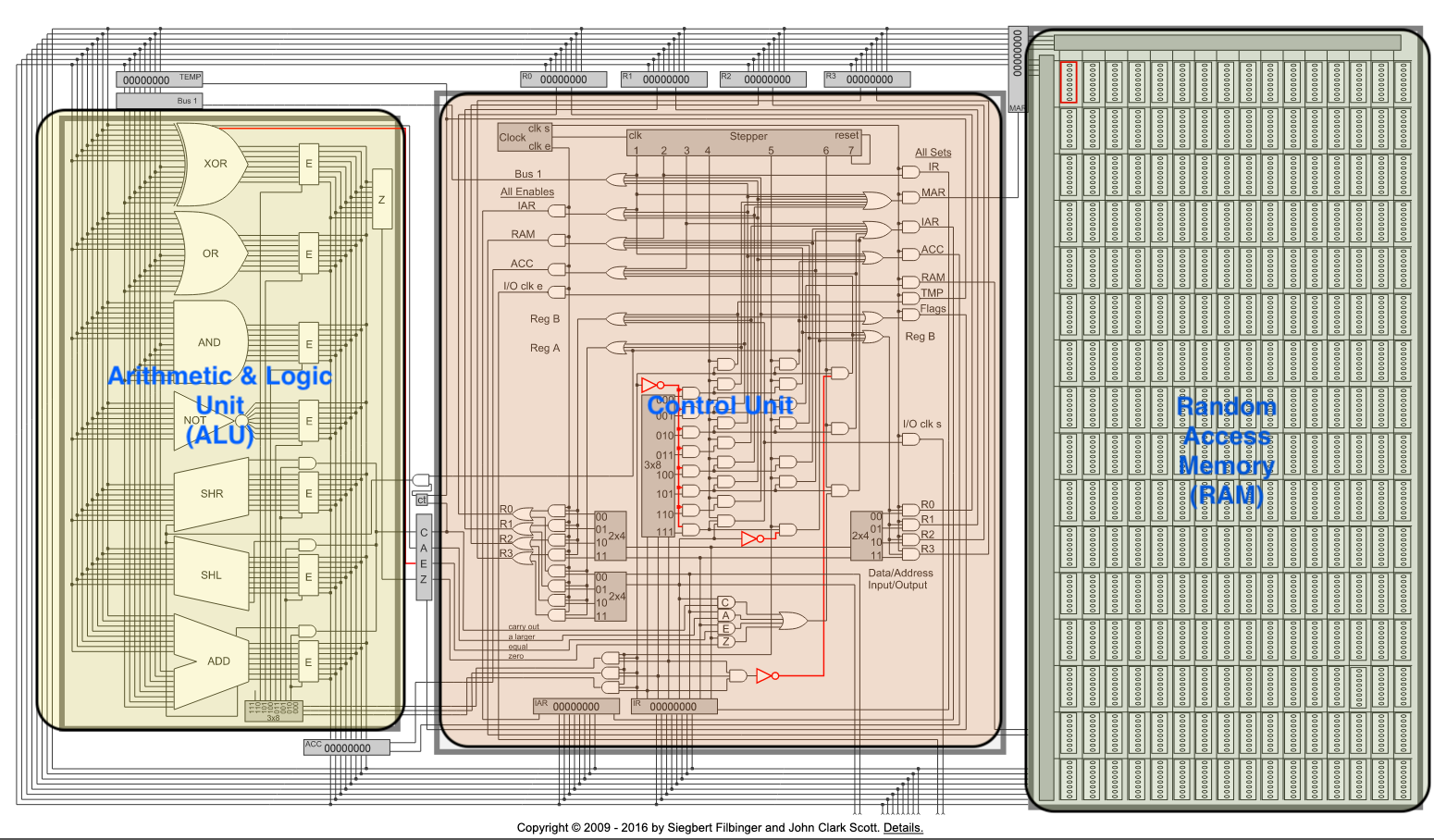

The Scott computer is an 8-bit processor attached to 256 bytes of RAM, all connected via an 8-bit system bus. It has 4 general purpose registers and can execute 17 machine instructions. Someone built a visual simulator for the web here, which is really cool, I dread to think how long it took to track all the wiring states!

A diagram outlining all the components that make up the Scott CPU

Copyright © 2009 - 2016 by Siegbert Filbinger and John Clark Scott.

The book takes you on a journey from the humble NAND gate, onto a Bit of memory, onto a register and then keeps layering on components until you end up with something resembling the above. I really recommend reading it, even if you are already familiar with the concepts because it’s quite a good overview. I don’t recommend the Kindle version though because the diagrams are sometimes hard to zoom in and decipher on a screen. A perennial problem for the Kindle in my experience.

The only thing that’s different about my computer is I upgraded it to 16-bit to have more memory to play with, as storing even just the glyphs for the ASCII table would have dwarfed most of the 8-bit machine described in the book, with not much room left for useful code.

My development journey

During development it really was just a case of reading the text, scouring the diagrams and then attempting to translate that using a general purpose programming language code and definitely not using something that’s designed for integrated circuit development. The reason why I wrote it in Go, is well, I know a bit of Go. Naysayers might chime in and say, you blithering idiot! I can’t believe you didn’t spend all your time learning VHDL or Verilog or LogSim or whatever but I’d already written my bits and bytes and NANDs by that point, I was in too deep. Maybe I’ll learn them next and weep about my time wasted, but that’s my cross to bear.

In the grand scheme of things most of the computer is just passing around a bunch of booleans, so any boolean friendly language will do the job.

Applying a schema to those booleans is what helps you (the programmer) derive its meaning, and the biggest decision anyone needs to make is decide what endianness your system is going to use and make sure all the components transfer things to and from the bus in the right order.

This was an absolute pain in the backside to implement. From the offset I opted for little endian but when testing the ALU my hair took a beating trying to work out why the numbers were coming out wrong. Many, many print statements took place on this one.

Development did take a while, maybe about a month or two during some of my free time, but once the CPU was done and successfully able to execute 2 + 2 = 5, I was happy.

Well, until the book discussed the I/O features, with designs for a simple keyboard and display interface so you can get things in and out of the machine. Well I’ve already gotten this far, no point in leaving it in a half finished state. I set myself a goal of being able to type something on a keyboard and render the letters on a display.

Peripherals

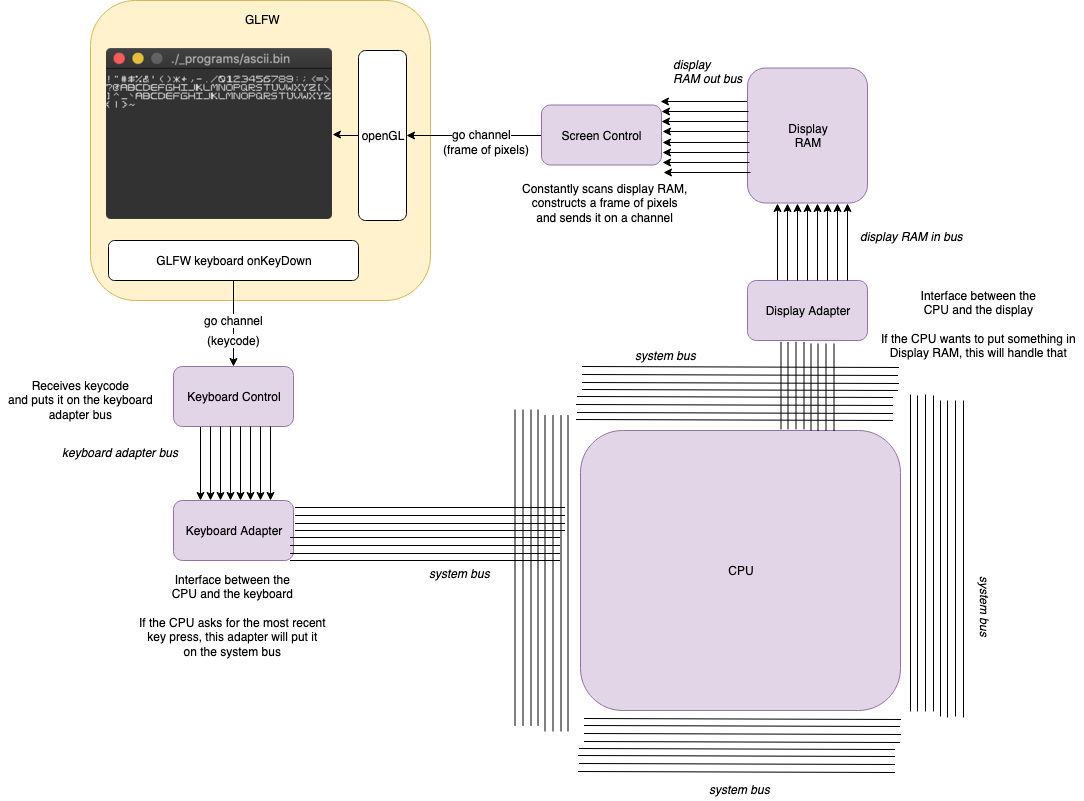

The peripherals use the adapter pattern to act as a hardware interface between the CPU and the outside world. It’s probably not a huge leap to guess this was what the software design pattern took inspiration from.

How the I/O adapters connect to a GLFW window

With this separation of concerns it was actually pretty simple to hook the other end of the keyboard and display to a window managed by GLFW. In fact I just pulled most of the code from my emulator and reshaped it a bit, using go channels to act as the signals in and out of the machine.

Bringing it to life

This was probably the most tricky part, or at least the most cumbersome. Writing assembly with such a limited instruction set sucks. Writing assembly using a crude assembler I wrote sucks even more because you can’t shake your fist at someone other than yourself.

The biggest problem was juggling the 4 registers and keeping track of them, pulling and putting stuff in memory as a temporary store. Whilst doing this I remembered the Gameboy CPU having a stack pointer register so you could push and pop state. Unfortunately this computer doesn’t have such a luxury, so I was mostly moving stuff in and out of memory on a bespoke basis.

The only pseudo instruction I took the time to implement was CALL to help calling functions, this allows you to run a function and then return to the point after the function was called. Without that stack though you can only call one level deep.

Also as the machine does not support interrupts, you have to implement awful polling code for functions like getting keyboard state. The book does discuss the steps needed to implement interrupts, but it would involve a lot more wiring.

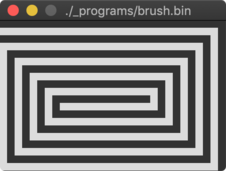

But anyway enough of the moaning, I ended up writing four programs and most of them make use of some shared code for drawing fonts, getting keyboard input etc. Not exactly operating system material but it did make me appreciate some of the services a simple operating system might provide.

It wasn’t easy though, the trickiest part of the text-writer program was getting the maths right to work out when to go to a newline, or what happens when you hit the enter key.

main-getInput:

CALL ROUTINE-io-pollKeyboard

CALL ROUTINE-io-drawFontCharacter

JMP main-getInputI didn’t get round to implementing the backspace key either, or any of the modifier keys. Made me appreciate how much work must go in to making text editors and how tedious that probably is.

On reflection

This was a fun and very rewarding project for me. In the midst of programming in the assembly language I’d largely forgotten about the NAND, AND and OR gates firing underneath. I’d ascended into the layers of abstraction above.

While the CPU in the is very simple and a long way from what’s sitting in my laptop, I think this project has taught me a lot, namely:

- How bits move around between all components using a bus

- How a simple ALU works

- What a simple Fetch-Decode-Execute cycle looks like

- That a machine without a stack pointer register + concept of a stack sucks

- That a machine without interrupts sucks

- What an assembler is and does

- How a peripherals communicate with a simple CPU

- How simple fonts work and an approach to rendering them on a display

- What a simple operating system might start to look like

So what’s next? The book said that no-one has built a computer like this since 1952, meaning I’ve got 67 years of material to brush up on, so that should keep me occupied for a while. I see the x86 manual is 4800 pages long, enough for some fun, light reading at bedtime.

Maybe I’ll have a brief dalliance with operating system stuff, a flirtation with the C language, a regrettable evening attempting to solder up a PiDP-11 kit then probably call it quits. I dunno, we’ll see.

With all seriousness though I think I’m going to start looking into RISC based stuff next, maybe RISC-V, but probably start with early RISC processors to get an understanding of the lineage. Modern CPUs have a lot more features like caches and stuff so I want to understand them as well. A lot of stuff out there to learn.

Do I need to know any of this stuff in my day job? Probably helps, but not really, but I’m enjoying it, so whatever, thanks for reading xxxx